So you are considering a PhD in robotics! Before you decide to apply, here are some things to consider.

What is a PhD?

A PhD is a terminal degree, meaning it is the highest degree that you can earn. Almost without exception, people only earn one PhD. This degree is required for some jobs, mostly in academia, but is often just considered equivalent to years worked in industry. For some positions, hiring managers may even prefer to hire people without PhDs. A PhD is a paid (though not well paid) position at a university that lasts for between 4 and 10 years. To learn more about the PhD process, check out this previous post.

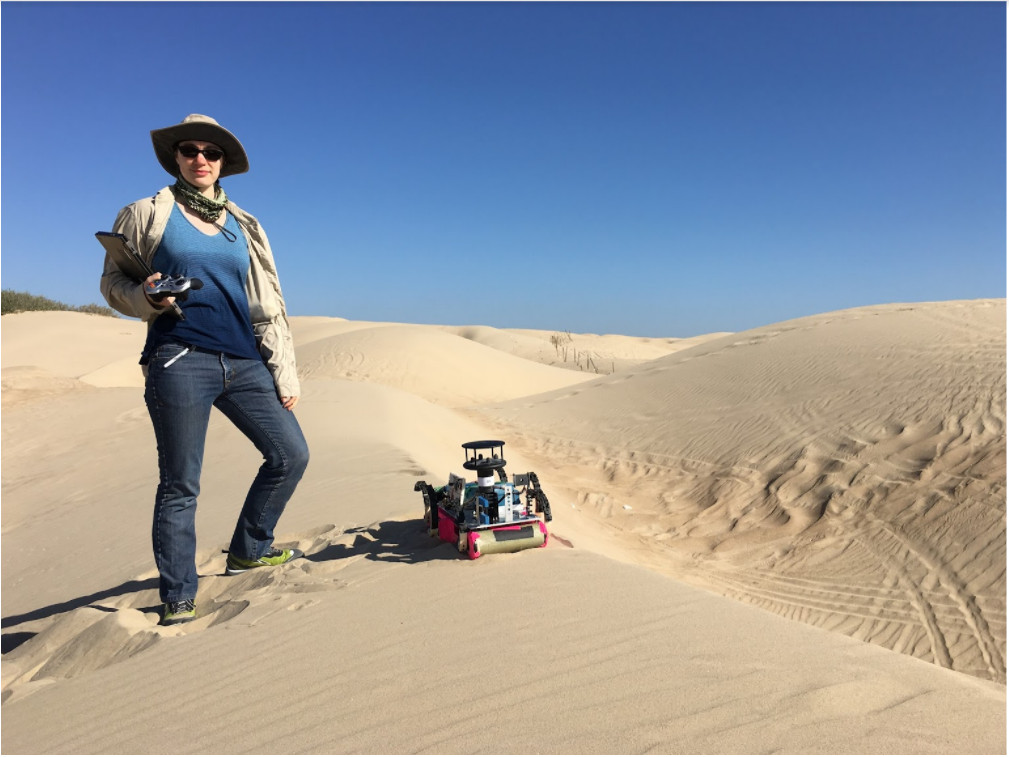

The author on a field trip to Oceano Dunes in California. She is controlling RHex, a six-legged robot, outfitted with sensors to study dune migration.

The day-to-day life of a PhD student versus an industry professional

The process of earning the PhD is very different from the process of earning a bachelor’s or a master’s degree. It is more like an internship or a job. The first two or so years of any PhD program will be largely coursework, but even at this stage you will be balancing spending time on your courses against spending time on research – either because you are rotating through different labs, because you are performing research for a qualifier, or because your advisor is attaching you to an existing research project to give you some experience and mentorship before you develop your own project. This means that getting a PhD is not actually a way to avoid “getting a job” or to “stay in school” – it is actually a job. This also means that just because you are good at or enjoy coursework does not mean you will necessarily enjoy or excel in a PhD program, and just because you struggled with coursework does not mean you will not flourish in a PhD program. After you are done with coursework, you will spend all of your time on research. Depending on the day, that can mean reading textbooks and research papers, writing papers, making and giving presentations, teaching yourself new skills or concepts, programming or building robots, running experiments, and mentoring younger students. If you excelled at either conducting research as an undergraduate or very open-ended course projects much more than typical coursework, you’ll be much more likely to enjoy research as a PhD student.

Types of goal setting in academia and industry

In course work, and in industry jobs with a good manager, you are given relatively small, well defined goals to accomplish. You have a team (your study group, your coworkers) who are all working towards the same goal and who you can ask for help. In a PhD program, you are largely responsible for narrowing down a big research question (like “How can we improve the performance of a self-driving car?”) into a question that you can answer over the course of a few years’ diligent work (“Can we use depth information to develop a new classification method for pedestrians?”). You define your own goals, often but not always with the advice of your advisor and your committee. Some projects might be team projects, but your PhD only has your name on it: You alone are responsible for this work. If this sounds exciting to you, great! But these are not good working conditions for everybody. If you do not work well under those conditions, know that you are no less brilliant, capable, or competent than someone who does. It just means that you might find a job in industry significantly more fulfilling than a job in academia. We tend to assume that getting a PhD is a mark of intelligence and perseverance, but that is often not the case — sometimes academia is just a bad match to someone’s goals and motivations.

Meaning and impact

Academic research usually has a large potential impact, but little immediate impact. In contrast, industry jobs generally have an impact that you can immediately see, even if it is very small. It is worth considering how much having a visible impact matters to you and your motivation because this is a major source of PhD student burnout. To give a tangible example, let’s say that you choose to do research on bipedal robot locomotion. In the future, your work might contribute to prostheses that can help people who have lost legs walk again, or to humanoid robots that can help with elder care. Is it important to you that you can see these applications come to fruition? If so, you might be more fulfilled working at a company that builds robots directed towards those kinds of tasks instead of working on fundamental research that may never see application in the real world. The world will be better for your contributions regardless of where you make them – you just want to make sure you are going to make those impacts in a way that allows you to find them meaningful!

Pay and lifetime earning potential

Engineers are significantly better paid in industry than academia. Since working in industry for a minimum of five to ten years and getting a PhD are often considered equivalent experience for the purposes of many job applications, even the time spent getting a PhD – where you will earn much less than you would in industry – can mean that you give up a substantial amount of money. Let’s say that an entry-level engineering job makes $100,000 per year, and a graduate student earns $40,000. If your PhD takes 6 years, you lose out on $60,000 x 6 = $360,000 of potential pay. Consider also that a PhD student’s stipend is fairly static, whereas you can expect to have incremental salary increases, bonuses, and promotions in an industry job, meaning that you actually lose out on at least $400,000. This is a totally valid reason to either skip the PhD process completely, or to work in industry for a few years and build up some savings before applying to PhD programs.

Robotics Institute at University of Toronto

How do I know what I want?

It’s hard! If you’re still uncertain, remember that you can gain a few years of work experience in industry before going back to get the PhD, and will likely be considered an even stronger candidate than before. Doing this allows you to build up some savings and become more confident that you really do want to get that PhD.

Thinking through these questions might help you figure out what direction you want to go:

- Are you much more motivated to do class projects that you are allowed to fully design yourself?

- When you think about something small you built being used daily by a neighbor, how do you feel?

- Is your desire to get a PhD because of the prestige associated with the degree, or the specific job opportunities it opens up?

Sonia Roberts

postdoc at Northeastern studying soft sensors

Women In Robotics

is a global community for women working in robotics, or who aspire to work in robotics

Women In Robotics

is a global community for women working in robotics, or who aspire to work in robotics

Credit: Source link

Comments are closed.