Researchers using the James Webb Space Telescope and the W. M. Keck Observatory have teamed up to study Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, and observe the way that clouds move around it. Early preview results of this research have now been released, which have not yet been peer-reviewed.

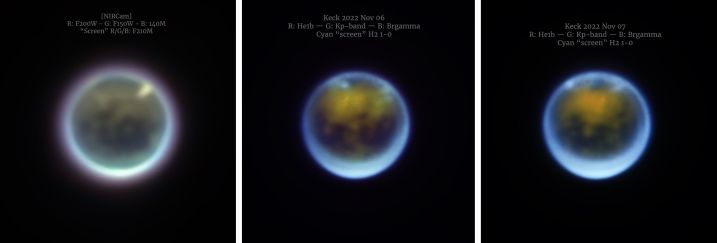

By bringing together space-based observations and ground-based observations, researchers were able to see how the clouds changed. Webb gathered data in the infrared using its Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) instrument, and Keck provided confirmation images also in the near-infrared two days later. “We were concerned that the clouds would be gone when we looked at Titan one and two days later with Keck, but to our delight there were clouds at the same positions, looking like they might have changed in shape,” said Keck researcher Imke de Pater in a statement.

The researchers were hoping to learn about Titan’s climate, and they found that there were large clouds in the moon’s northern hemisphere. “Detecting clouds is exciting because it validates long-held predictions from computer models about Titan’s climate, that clouds would form readily in the mid-northern hemisphere during its late summertime when the surface is warmed by the Sun,” said lead researcher Conor Nixon. Some of these clouds are located near Kraken Mare, a sea of liquid methane on the moon’s surface.

Titan is of interest to astronomers because of its thick atmosphere, and because it has lakes, rivers, and oceans on its surface. But unlike Earth, these features are made of liquid methane rather than water. The amount of liquid means that Titan could even be a place to look for signs of life, and there is interest in sending a submarine probe there.

There are also plans to send a rotorcraft called Dragonfly to explore the moon, currently set for launch in 2027. Observations like these recent ones from Webb and Keck help prepare the way for this mission.

“This is some of the most exciting data we have seen of Titan since the end of the Cassini-Huygens mission in 2017, and some of the best we will get before NASA’s Dragonfly arrives in 2032,” said Dragonfly’s principal investigator, Zibi Turtle. “The analysis should really help us to learn a lot about Titan’s atmosphere and meteorology.”

Editors’ Recommendations

Credit: Source link

Comments are closed.