When President Joe Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) into law on August 16, 2022, we started looking into its implications, particularly with regard to the impact on the future of the climate and the innovations that might shape that future.

As the most important piece of climate legislation in United States history, the IRA represents a fundamental regulatory inflection that may help create a different future. The purpose of this post is to share our understanding of the regulatory ramifications of this monumental bill, especially as they relate to the problems some of the most capable founders in the world are looking to tackle.

Building electrification

The IRA contains several major programs that aim to accelerate building electrification — the replacing of residential fossil fuel machines with electric equivalents. This has the benefit of eliminating combustion emissions, improving comfort, as well as improving indoor air quality, which can have dramatic positive health impacts.

There are three major programs that incentivize building electrification. The first (Sec. 50122) provides a total of $4.5 billion in funding for appliance replacements and is means tested: It provides up to 100% of project costs for those earning less than 80% of area median income (AMI) and 50% of project costs for those earning less than 150% AMI, with annual limits. Eligible appliances include heat pumps, heat pump water heaters, electric or induction stoves, electric or heat pump clothes dryers, upgraded breaker boxes, electrical wiring upgrades, home energy audits, and insulation and sealing.

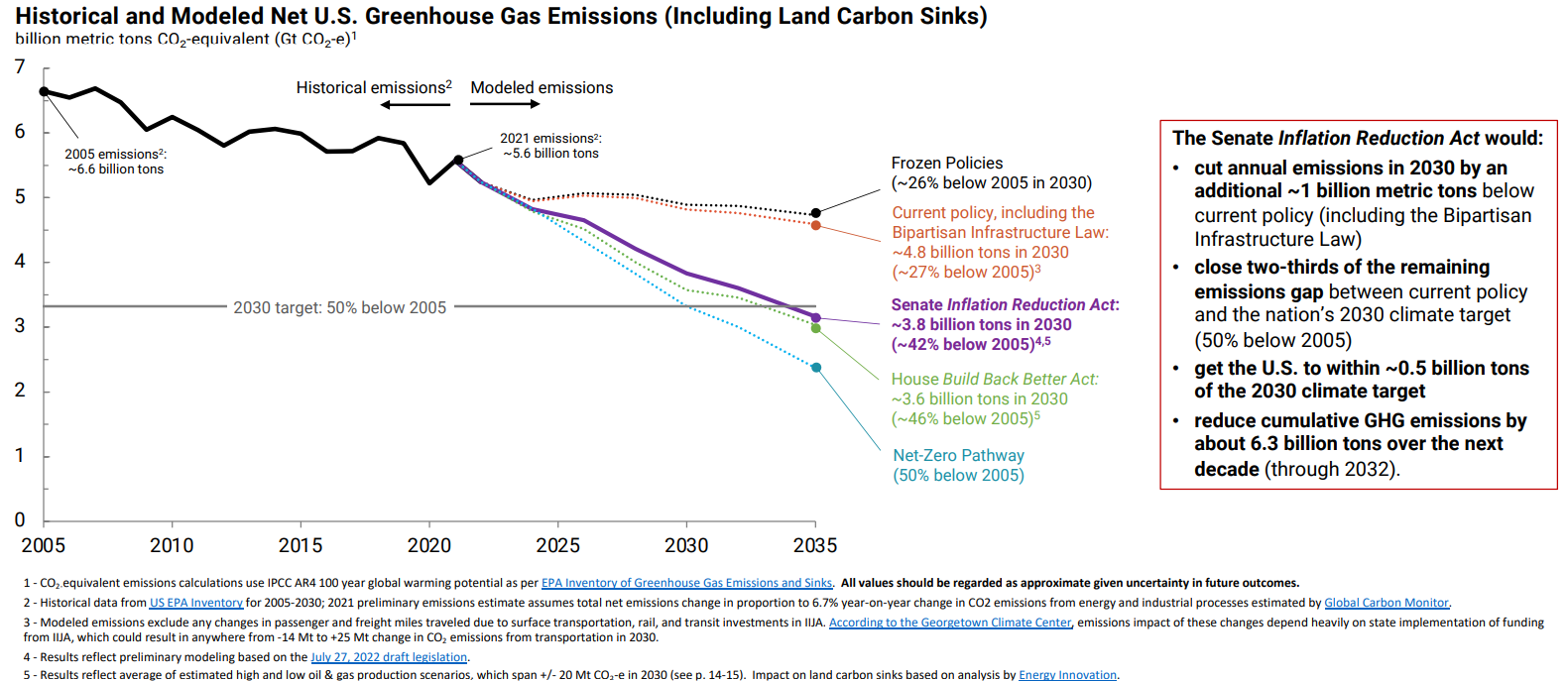

Image Credits: REPEAT Project

The second program (Sec. 50121) is a performance-based home energy retrofit program that provides up to $4,000 per home, or $8,000 per home for low-to-moderate income households. Projects cannot claim both this program and Sec. 50122.

To gauge long-term regulatory impact, it is worthwhile to look to the EU, which continues to play a leading role in the evolving global climate policy.

Both programs can be combined with the third program (Sec. 13302), which expands the Investment Tax Credit (ITC) to a 30% tax credit for eligible projects including residential solar, solar water heating, fuel cell, small wind energy, battery storage and geothermal heat pumps.

The IRA also includes significant and open-ended financing for projects that broadly reduce greenhouse gasses and accelerate deployment of renewable energy, many of which will likely apply to building electrification projects, such as the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (Sec. 60103), and $40 billion in loan guarantee authority for the Department of Energy (Sec. 50141).

Interesting problems

The funding in the IRA for buildings is likely to catalyze the replacement of fossil fuel machines in buildings and accelerate the adoption of fully electric alternatives. Today, market share of these alternatives is relatively low and contractor adoption and expertise is lacking. Early examples of an increase in consumer demand for these products include Maine and New York.

While we won’t see an overnight shift across the country, these incentives will create a burgeoning market for home electrification, similar to how past laws created a market for residential solar. Problems we have identified include:

- Fragmented contractor market.

- There are not enough trained professionals (electricians, HVAC technicians, etc.).

- Projects tend to be highly custom and time intensive to design and quote.

- Difficult for businesses and consumers to navigate the changing financing/incentives landscape.

- The ROI of these projects will be highly variable and vary from home to home.

- Most home appliances are replaced on failure in an emergency, and most homes are not wired for 220v, so there is a pre-wiring problem to be solved.

- Navigating the retrofit process is time consuming and confusing for consumers, requiring work across multiple contractors that don’t individually plan for holistic project needs (e.g., panel upgrade).

Carbon capture/methane reduction

The latest science tells us that in order to keep warming to 1.5°–2° C, we need to reduce emissions to about 45% lower than 2010 levels by 2030 and achieve net-zero by 2050. It is not realistic to expect that we can replace all of our fossil fuel machines and processes in that time frame.

Credit: Source link

Comments are closed.