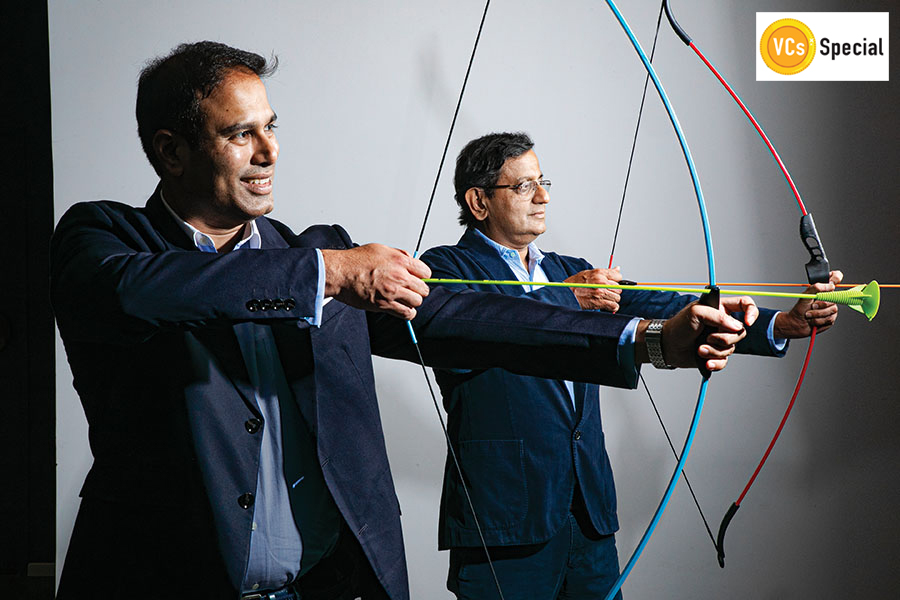

Mohan Kumar (right) and Nishant Rao, co-founders, Avataar Venture Partners

Mohan Kumar (right) and Nishant Rao, co-founders, Avataar Venture Partners

Who is a seasoned investor? Is it someone who has backed multiple ventures? Or a veteran who has seen various investment cycles—hypes and bubbles—over decades? Mohan Kumar ticks both the boxes, but what really qualifies him as a seasoned investor is a trait that not many in the investment world possess: Balanced storytelling. He starts with a tale where the protagonist is a founder.

Once upon a time—well, it was in the middle of last year—the startup ecosystem in India found itself in the midst of a crazy funding boom. Kumar, who has spent two decades in leadership and operating roles, including as corporate vice president of Motorola, and has also had stints with two startups, describes the ‘insane’ funding scene. Pre-2018, he first sets the context, the valuation multiples for SaaS companies were in the range of seven to 10 times their revenue. “If you happened to be a market leader, you could even get 15 times,” says the former managing partner at Norwest Venture Partners (NVP), who started growth-stage SaaS- and B2B-focussed fund Avataar Venture Partners towards the latter part of 2019. During the peak of the pandemic, SaaS companies started getting 40x. “Some even got 100x,” he says with a smile.

The reason was simple. The pandemic shut down everything and software companies, and many others who were riding the pandemic tailwinds, were the vaccine the world badly needed. The hedge funds, for instance, the much-famed Tiger Global and the likes, suddenly realised that they were missing the party. “They gatecrashed,” he says. The funding narrative changed. Suddenly, the companies that were raising $30 million for a 20 percent dilution, let’s say, started getting $100 million or $200 million for the same 20 percent. There was hardly any due diligence, and the only objective was to get in, whatever the price.

The findings were interesting. A SaaS company in the US roughly spends $1 to acquire 50 cents of revenue. And a $100-million company raises around $150-200 million. Other findings were equally interesting. The SaaS companies raise money, and spend heavily on sales and marketing. “The average spend on sales and marketing for SaaS companies is about 60 percent of the revenue,” says Kumar.

The findings, when put in the Indian context, meant two things. First, for every $1 of revenue, one should do a maximum of $1 of capital raise. So if one wants to cross $100 million, then one should not raise more than $100 million. Now, in India, Kumar points out, a SaaS company usually has raised $20-$25 million till Series B, and would have had $10-$15 million in revenue. “Avataar decided to cut a cheque size of $30-$35 million,” says Kumar. The money, he adds, would be enough to take such companies past $60 million or $70 million. And the ones more disciplined with capital might also touch $100 million in revenue with the funding. “This was the hypothesis,” he says.

The VC, though, doesn’t blame the founder for going with the inflated offer. As a founder, Kumar underlines, one has a responsibility not to reject a high-value round. “It’s not prudent. One must take money,” he says. But it’s a package deal. The founder must also realise that she has been paid a high premium, which is not normal. “So you need to live up to the expectation,” he says. What this means is that one must not waste money, and must use it prudently. The problem, though, is 80 percent of the founders do the first part, but forget about the second. Money goes into higher salaries, unnecessary expansion and other avoidable costs. Once the runway gets alarmingly short, and the funding climate gets hostile, the founder and her firm stares at an impending disaster.

So can we blame the funders for spoiling the market? “No,” says Kumar. “Could a Flipkart or Ola have ever dared to take on Uber or Amazon if they were not loaded with money?” he asks. The big money, Kumar underlines, was there to do big and think big. “Founders took the money and then messed it up,” he says. The investors, if at all one has to put them on the mat, could be held responsible for not putting in enough checks and balances, and enforcing high governance standards.

Excess capital brought in its wake another set of problems. “A lot of fake entrepreneurs jumped into the fray,” reckons Kumar. Before 2014, it was not easy to start up and raise money. People would think 100 times before leaving a large corporate and joining or starting up on their own. “Startups were only meant for the brave ones. The ones who had loads of passion and who could hustle hard,” he says. Once capital became easy flowing, everybody jumped in. “You could not distinguish between the real and fake ones. Everybody got funded,” he contends. And when things went south, take for instance the present funding winter, the first people to bail out and falter are the ones who didn’t have the passion.

When Avataar invested in Capillary, a loyalty SaaS player, the only pre-condition was that the startup move beyond India. The reason was scale. An interesting thing about SaaS, he points out, is that it’s highly unlikely that one can build a great company just focusing on India or Asia. “If you look at 100 successful SaaS companies, 90 would have cracked the US market,” he says.

Founders, he lets on, at this stage of their journey value the pedigree of an investor more than the money. Pumping in money is easy, but doing what money can’t do is the art. Back in 2018, there was only one, Freshworks, with over $100 million. “Last year, there were at least 10 companies that crossed $100 million,” he claims. And over 50, he adds, are above $20 million. “The SaaS ecosystem is very healthy and growing,” he says. “And it’s a great time to be a SaaS investor and founder.”

Check out our Festive offers upto Rs.1000/- off website prices on subscriptions + Gift card worth Rs 500/- from Eatbetterco.com. Click here to know more.

Credit: Source link

Comments are closed.