In “The Power Law,” Journalist Sebastian Mallaby Explores the “Intellectual Mystery” of Venture Capital

Published on

(iStock/Yermek Aitkuzhin)

All investing is a bet on uncertainty. But venture capital investing, often in fledgling companies without cash flow or any proof of viability, is so uncertain as to be an “intellectual mystery” – and that is what drew British journalist Sebastian Mallaby to write a seminal book exploring the nuances of the VC game.

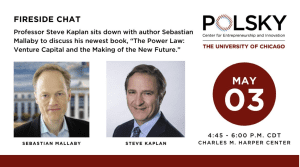

Mallaby, author of “The Power Law: Venture Capital and the Making of the New Future,” recently sat down with Randall Kroszner, deputy dean for executive programs at Chicago Booth and Norman R. Bobins Professor of Economics, to discuss his new book and what he learned by immersing himself in Silicon Valley’s leading venture capital firms.

Kroszner was conducting the interview on behalf of private equity scholar Steven Kaplan, Neubauer Family Distinguished Service Professor of Entrepreneurship and Finance at Booth, who was out sick but conveyed a hearty endorsement of Mallaby’s work: “I learned more about venture capital from Sebastian’s book than from any other book I have read,” Kaplan said.

Kroszner was conducting the interview on behalf of private equity scholar Steven Kaplan, Neubauer Family Distinguished Service Professor of Entrepreneurship and Finance at Booth, who was out sick but conveyed a hearty endorsement of Mallaby’s work: “I learned more about venture capital from Sebastian’s book than from any other book I have read,” Kaplan said.

Mallaby, the Paul A. Volcker senior fellow for international economics at the Council on Foreign Relations, told Kroszner he had misgivings when he first dove into Silicon Valley culture.

“It seemed absurdly superficial and it seemed like the whole thing was a casino,” Mallaby said, recounting how one VC chose to invest because the founder shared his love of biking and many deals seemed based on little more than good vibes.

“Eventually I was able to see through that nonsense and understand the real reasons why there is skill in this sector, why some do well and some do badly,” he said.

A distinctive VC skill is thinking differently about how to assess risk. VCs gamble for the upside, assuming most investments will fail but a few will perform so well that they will make up for all the losses, so “the risk is that you fail to bet on something that does really well,” Mallaby said.

That’s the essence of the “power law” that motivates the venture capital machine to back audacious but potentially transformative businesses: “The rewards for success will be massively greater than the costs of honorable setbacks,” is how Mallaby sums up the logic in his book.

That’s the essence of the “power law” that motivates the venture capital machine to back audacious but potentially transformative businesses: “The rewards for success will be massively greater than the costs of honorable setbacks,” is how Mallaby sums up the logic in his book.

Another key feature of the VC mindset is preparation. They must see not only what new tech is coming but also what kinds of new companies will need to be formed as a result, so that they can operate at the same speed as visionary founders.

“When cloud computing came on horizon, the best VCs, when they met an entrepreneur, they could complete their sentences before they could finish,” Mallaby said. “It shows that you are on their wavelength, so they are more likely to accept your investment.”

VC firms often balance the investment risk by taking a seat on their portfolio companies’ boards. But there are differing views on how much guidance VCs should provide.

Legendary investor Peter Thiel advises a hands-off approach that allows the idiosyncratic startup founder to run the show, because “to have a shot at greatness you have to be a bit weird, you have to be a bit different, and the last thing you want is for them to be homogenized by a venture capital grownup,” Mallaby said.

But Mallaby offers cautionary examples, such as Uber, when investor guidance could have averted crisis. He favors a more interventionist approach that encourages VC investors to step in to ensure founder eccentricities do not seep into areas they shouldn’t, such as legal or accounting. Knowing when and how to intervene, and having the emotional intelligence to communicate guidance effectively, makes for successful VC relationships, he said.

“Part of the trick with being a great VC is that you invest in different companies and you should be an advisor in a different way for different founders,” Mallaby said. “Some are very aggressive and want to grow too fast; you want to calm them down. Some are too cautious; you want to speed them up.”

Credit: Source link

Comments are closed.