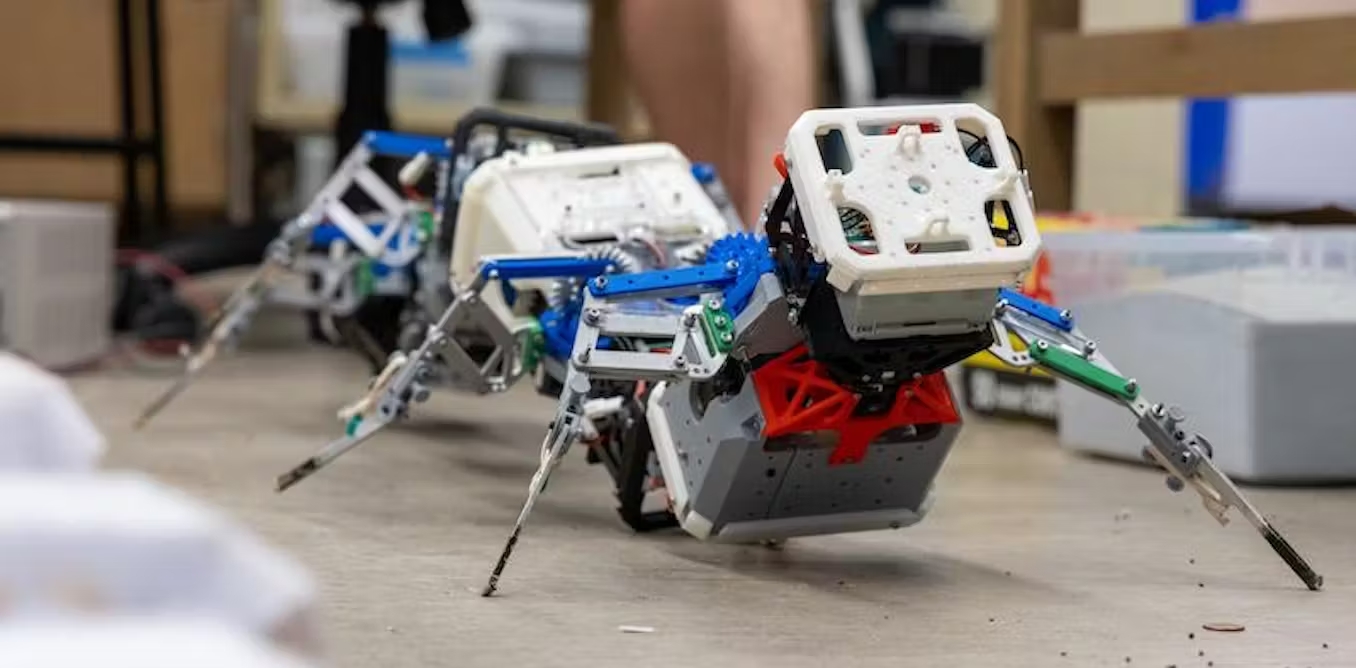

Getting a leg up from mobile robots comes down to getting a bunch of legs. Georgia Institute of Technology

By Baxi Chong (Postdoctoral Fellow, School of Physics, Georgia Institute of Technology)

Adding legs to robots that have minimal awareness of the environment around them can help the robots operate more effectively in difficult terrain, my colleagues and I found.

We were inspired by mathematician and engineer Claude Shannon’s communication theory about how to transmit signals over distance. Instead of spending a huge amount of money to build the perfect wire, Shannon illustrated that it is good enough to use redundancy to reliably convey information over noisy communication channels. We wondered if we could do the same thing for transporting cargo via robots. That is, if we want to transport cargo over “noisy” terrain, say fallen trees and large rocks, in a reasonable amount of time, could we do it by just adding legs to the robot carrying the cargo and do so without sensors and cameras on the robot?

Most mobile robots use inertial sensors to gain an awareness of how they are moving through space. Our key idea is to forget about inertia and replace it with the simple function of repeatedly making steps. In doing so, our theoretical analysis confirms our hypothesis of reliable and predictable robot locomotion – and hence cargo transport – without additional sensing and control.

To verify our hypothesis, we built robots inspired by centipedes. We discovered that the more legs we added, the better the robot could move across uneven surfaces without any additional sensing or control technology. Specifically, we conducted a series of experiments where we built terrain to mimic an inconsistent natural environment. We evaluated the robot locomotion performance by gradually increasing the number of legs in increments of two, beginning with six legs and eventually reaching a total of 16 legs.

Navigating rough terrain can be as simple as taking it a step at a time, at least if you have a lot of legs.

As the number of legs increased, we observed that the robot exhibited enhanced agility in traversing the terrain, even in the absence of sensors. To further assess its capabilities, we conducted outdoor tests on real terrain to evaluate its performance in more realistic conditions, where it performed just as well. There is potential to use many-legged robots for agriculture, space exploration and search and rescue.

Why it matters

Transporting things – food, fuel, building materials, medical supplies – is essential to modern societies, and effective goods exchange is the cornerstone of commercial activity. For centuries, transporting material on land has required building roads and tracks. However, roads and tracks are not available everywhere. Places such as hilly countryside have had limited access to cargo. Robots might be a way to transport payloads in these regions.

What other research is being done in this field

Other researchers have been developing humanoid robots and robot dogs, which have become increasingly agile in recent years. These robots rely on accurate sensors to know where they are and what is in front of them, and then make decisions on how to navigate.

However, their strong dependence on environmental awareness limits them in unpredictable environments. For example, in search-and-rescue tasks, sensors can be damaged and environments can change.

What’s next

My colleagues and I have taken valuable insights from our research and applied them to the field of crop farming. We have founded a company that uses these robots to efficiently weed farmland. As we continue to advance this technology, we are focused on refining the robot’s design and functionality.

While we understand the functional aspects of the centipede robot framework, our ongoing efforts are aimed at determining the optimal number of legs required for motion without relying on external sensing. Our goal is to strike a balance between cost-effectiveness and retaining the benefits of the system. Currently, we have shown that 12 is the minimum number of legs for these robots to be effective, but we are still investigating the ideal number.

The Research Brief is a short take on interesting academic work.

![]()

The authors has received funding from NSF-Simons Southeast Center for Mathematics and Biology (Simons Foundation SFARI 594594), Georgia Research Alliance (GRA.VL22.B12), Army Research Office (ARO) MURI program, Army Research Office Grant W911NF-11-1-0514 and a Dunn Family Professorship.

The author and his colleagues have one or more pending patent applications related to the research covered in this article.

The author and his colleagues have established a start-up company, Ground Control Robotics, Inc., partially based on this work.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Conversation

is an independent source of news and views, sourced from the academic and research community and delivered direct to the public.

The Conversation

is an independent source of news and views, sourced from the academic and research community and delivered direct to the public.

Credit: Source link

Comments are closed.