Ashish Sharma, CEO, InnoVen Capital India

Ashish Sharma, CEO, InnoVen Capital India

Image: Madhu Kapparath In 2017, when Ashish Sharma was taking a fresh guard, the financial market veteran found something weird about the startup pitch on which he was about to play his new innings. The track looked dry and it did not have blades of grass. After spending two decades with GE Capital, where he was president and chief executive officer (CEO) for a good three years between 2014 and 2017, Sharma joined venture debt fund InnoVen Capital as the CEO. As an outsider venturing into the startup world, he had one big comfort factor. His previous company and the new one, both had the word ‘Capital’ in their names. The similarities, however, ended right there.

The game at InnoVen was insanely different. Sharma explains. At GE Capital, there were thousands of people reporting to the CEO and the lending business was growing at a brisk pace. The ‘push and pull’ worked brilliantly as the lender and the borrower understood the need, and the rules of the game. GE Capital, as a brand name, was massive. Familiarity and credibility worked like a flywheel. At InnoVen, in 2017, Sharma struggled to make founders aware of the need to raise venture debt. Four years ago, India was in the thick of intense funding activity, and founders loved venture capital (VC) for two reasons. First, it brought instant money for growth. Second, founders have mentors on board to counsel according to their needs.“Why should I raise venture debt when I have venture capital,” was one of the bouncers bowled at Sharma. The bowlers, interestingly, happened to entrepreneurs who had raised loads of venture capital and were on track to becoming a unicorn, being valued at $1 billion-plus (over Rs 7,500 crore). For most of them, debt happened to be a dirty word that carried negative connotations. “What if I do not pay back on time? Would you guys take over my business,” asked one of founders of a soonicorn [soon-to-be-unicorn] startup.

At InnoVen, in 2017, Sharma struggled to make founders aware of the need to raise venture debt. Four years ago, India was in the thick of intense funding activity, and founders loved venture capital (VC) for two reasons. First, it brought instant money for growth. Second, founders have mentors on board to counsel according to their needs.“Why should I raise venture debt when I have venture capital,” was one of the bouncers bowled at Sharma. The bowlers, interestingly, happened to entrepreneurs who had raised loads of venture capital and were on track to becoming a unicorn, being valued at $1 billion-plus (over Rs 7,500 crore). For most of them, debt happened to be a dirty word that carried negative connotations. “What if I do not pay back on time? Would you guys take over my business,” asked one of founders of a soonicorn [soon-to-be-unicorn] startup.

Sharma knew ducking the ball was not an option. Though startup founders knew InnoVen, they were hesitant about taking the leap of faith. There were many queries, apprehensions and misconceptions around debt. Sharma went on to the back foot, only to convincingly hook each query out of the park. “Why do Tatas and Birlas have debt on their book,” he asked a startup co-founder in 2017. “Do you think they cannot raise equity,” he underlined. The second counter-argument packed more punch. Quick capital, low rate of interest, and almost negligible dilution of equity. “It is not why you need venture debt, it is why not have it,” he told them.

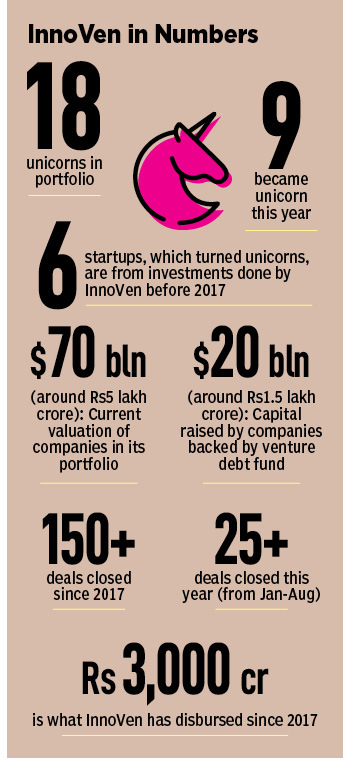

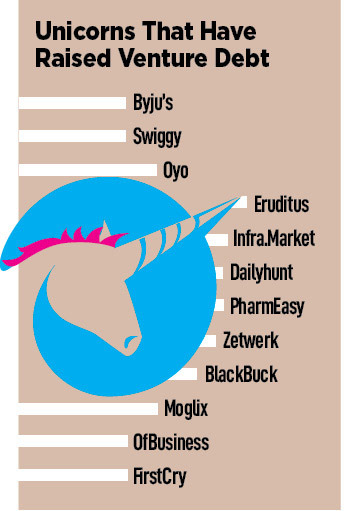

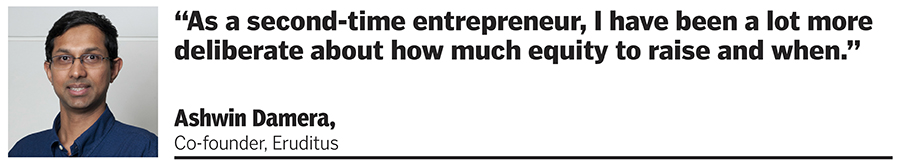

Almost at the same time, a bunch of seasoned entrepreneurs—most into their second venture—had learnt a valuable lesson the hard way: One must not dilute too much in one’s startup. Ashish Damera, co-founder of edtech startup Eruditus, which turned unicorn in August this year, explains the flip side of raising too much capital. “As a second-time entrepreneur, I have been a lot more to deliberate about how much equity to raise and when, as this impacts dilution,” he says. In July 2018, Damera reportedly raised venture debt of Rs19 crore from InnoVen Capital. Till then, Eruditus had raised a paltry $8 million (Rs 60 crore) in Series B in 2017, and was valued at $50 million (Rs360 crore).Venture debt turned out to be a tailwind for Damera. “It extended the runway before going for an equity fundraise,” he recalls. It also gave, he explains, more time to hit higher milestones and getter better financing outcomes. In August, when Eruditus turned unicorn, the co-founders still had 40 percent stake in the company. “InnoVen has been a great partner, and together we have done many transactions over the years,” he says. The familiarity helped in moving fast whenever there is an urgent need. For example. Earlier this year, when Eruditus needed some liquidity cushion to move quickly on an acquisition, InnoVen pumped in $20 million (Rs150 crore). Eruditus is not the only unicorn to add InnoVen’s debt to its growth story. There are more like edtech startup Byju’s, hotel chain Oyo, local language news aggregator Dailyhunt and online freight aggregator BlackBuck (see box) who have raised venture debt from the oldest and biggest venture debt player in India. “Overall, we have 18 unicorns in our portfolio. In fact, nine became unicorns this year,” says Sharma, who loves Virender Sehwag’s style of batting.

Eruditus is not the only unicorn to add InnoVen’s debt to its growth story. There are more like edtech startup Byju’s, hotel chain Oyo, local language news aggregator Dailyhunt and online freight aggregator BlackBuck (see box) who have raised venture debt from the oldest and biggest venture debt player in India. “Overall, we have 18 unicorns in our portfolio. In fact, nine became unicorns this year,” says Sharma, who loves Virender Sehwag’s style of batting.

The CEO, however, explains why Sehwag’s aggressive and hard-hitting style is not suited for venture debt. The not-so-glamourous cousin of venture capital, Sharma underlines, needs loads of patience. Venture debt, Sharma stresses, is more akin Rahul Dravid’s style of batting, which involves a lot of singles and occasional boundaries.

What ‘quick singles’ means is taking money, returning it with interest and then taking more money. “What venture [debt] brings to the table is a lesser diluted way of financing business,” Sharma points out, adding a quick disclaimer. “Frankly, we do not substitute equity,” he says. For any startup that needs to raise venture debt, he explains, the pre-requisite is a previous round of venture capital. “We do not give money to companies that have not raised equity.”For those who think that venture debt fund means zero equity in the startups, there is a surprise. Tarana Lalwani, senior director at InnoVen Capital, explains that venture debt deals are structured to include a small equity component (typically 10-12 percent of the loan amount), which gives the lender the right to invest in the company and generate additional returns on a portfolio basis. Equity kicker, in short, takes care of the risk that the fund is taking while betting on the future performance of companies.

Meanwhile, unicorns, soonicorns and all kinds of startups do not mind an equity kicker and adding debt to their venture story. Reasons include less dilution, additional capital to grow faster, ability to extend runway, and hit milestones before raising the next round of capital at a much higher valuation. The use cases can be working capital, growth investments, capital expenditure, acquisitions, contingency fund; tenure to repay is between 2 and 3 years, and interest rate varies between 14-15 percent.***

Venture debt traces its origin to 1970s in the US. Back then, startups in the Silicon Valley needed financing for equipment, computers, hardware but could not get bank loans as they did not fit the traditional lending criteria. Most of them did not have a track record, were loss-making, often lacked predictable cash flows to service the debt and could not offer the type of collateral banks preferred, explains Sharma. Specialised finance players saw the opportunity and started offering equipment loans and leases to these companies. Over time, this evolved into a full-fledged venture debt industry where debt was available for a variety of use cases.

In India, Virendra Gupta, founder of VerSe Innovation, the parent company of Dailyhunt and short-video platform Josh, latched on to venture debt to maintain growth momentum. According to him, a business like his requires a lot of investments to build infrastructure capabilities and to attract new users. In addition to raising equity capital, which happens every 12-18 months, the company took venture debt to maintain growth momentum. “InnoVen was our first institutional debt investor, and over the years, the teams have executed several transactions,” he says. They understand our business and are able to move fast, whenever we needed additional debt capital, Gupta explains.

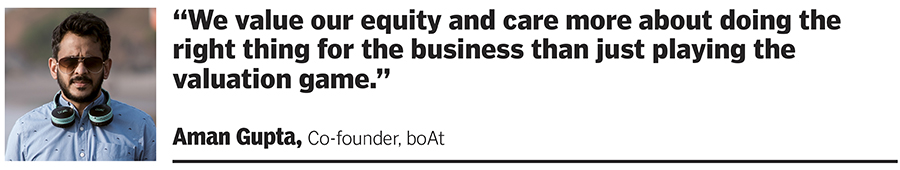

InnoVen has grown at a brisk pace: Over Rs900 crore disbursed over the last nine months. Compare this to Rs650 crore between FY17 and FY20 and Rs300 crore from FY15 to FY17. “We are seeing higher level of demand for venture debt over the last year as most startups have enjoyed tailwinds after Covid-19 and [are] focusing on growth,” says Sameer Mansukhani, senior director at InnoVen Capital. There is more supply of equity as well as debt capital in the market, which is a positive for the ecosystem, according to him.For Aman Gupta, co-founder of consumer electronics brand boAt, the biggest positive of going into ‘debt’ was staying away from the valuation game. Now-a-days, he says, entrepreneurs become more focussed on valuations rather than preserving equity, and thereby dilute more than required. “We value our equity and care about doing the right things than just playing the valuation game,” he says, adding that the startup raised Rs16 crore from InnoVen in 2019. This January, boAt raised $100 million (Rs700 crore) from private equity firm Warburg Pincus at a valuation of Rs2,000 crore, and the co-founders still have over 51 percent stake in the company. “More stake means deeper skin in the game,” he says.Sharma, for his part, reckons that though venture debt has been galloping over the last two years, it is still early days. “While VCs play like Sehwag, we need to keep batting like Dravid,” he smiles.

InnoVen has grown at a brisk pace: Over Rs900 crore disbursed over the last nine months. Compare this to Rs650 crore between FY17 and FY20 and Rs300 crore from FY15 to FY17. “We are seeing higher level of demand for venture debt over the last year as most startups have enjoyed tailwinds after Covid-19 and [are] focusing on growth,” says Sameer Mansukhani, senior director at InnoVen Capital. There is more supply of equity as well as debt capital in the market, which is a positive for the ecosystem, according to him.For Aman Gupta, co-founder of consumer electronics brand boAt, the biggest positive of going into ‘debt’ was staying away from the valuation game. Now-a-days, he says, entrepreneurs become more focussed on valuations rather than preserving equity, and thereby dilute more than required. “We value our equity and care about doing the right things than just playing the valuation game,” he says, adding that the startup raised Rs16 crore from InnoVen in 2019. This January, boAt raised $100 million (Rs700 crore) from private equity firm Warburg Pincus at a valuation of Rs2,000 crore, and the co-founders still have over 51 percent stake in the company. “More stake means deeper skin in the game,” he says.Sharma, for his part, reckons that though venture debt has been galloping over the last two years, it is still early days. “While VCs play like Sehwag, we need to keep batting like Dravid,” he smiles.

Click here to see Forbes India’s comprehensive coverage on the Covid-19 situation and its impact on life, business and the economy

Credit: Source link

Comments are closed.