In October 2021, when tech-enabled logistics platform Porter raised Rs 750 crore in Series E funding from Tiger Global and Vitruvian Partners, it announced the consolidation of another start-up in the logistics space that is likely to hit the market size of $380 billion by 2025. This soonicorn rivals companies like Delhivery, the market leader whose valuation rose to $4.89 billion when it went public, and Xpressbees, which became a unicorn in February last year when it raised $300 million in the Series F funding round.

Logistics start-ups are the latest entrants to India’s unicorn wave, where investors are betting on the sector’s potential, as they are wont, rather than the profit it generates. Porter last declared its losses for 2019–20, which had increased from Rs 41.4 crore in the previous year to Rs 104.1 crore on a revenue of Rs 275.79 crore. It declared a revenue of Rs 862 crore in FY22 without commenting on the profit or loss for the period. On the other hand, market leader Delhivery posted a loss of Rs 254 crore in the second quarter of FY23 on a revenue of Rs 1,796 crore.

The story of India’s logistics sector has the same moral irrespective of the company from whose perspective it is told. Clearly, the tech-enabled platformisation of this sector, which is as mammoth as it can get in India, is being underwritten by institutional investors for the promise of future gains.

The elusive promise of future, however, is a feature of the digital business in India that goes beyond just one sector. The digital economy that has the ambition to touch the value of one trillion dollars by 2025—this is what Prime Minister Narendra Modi told the BRICS Business Forum in June last year—comprises examples which do not have clear profit goals in sight. This trend is most visible in start-ups and established players which had heralded digital disruption in their respective areas of operation in India but are struggling to create a sustainable profit-driven model that can give value to their investors.

Missing Profits of Copycat Products

The product-driven digital companies started making it big in India towards the end of the first decade of the 21st century. Some of the earliest digital and consumer-tech companies have had a run for a decade and a half by now, but they have not discovered the profit route yet, even when their revenue and valuation keep going up. A lot of these companies started by claiming disruption in the traditional way of doing the same business using the internet, but their ability to monetise the disruption remains questionable.

Take, for example, the case of MakeMyTrip. Founded in 2000, it became the first unicorn of India in 2010 in the start-up space. It cloned Booking.com and the Expedia Group from Western markets and rode on the investments from Tiger Fund and Helion Venture Partners and then took the IPO route on Nasdaq in its valuation journey. After raising $748 million in six funding rounds and merging with its rival Ibibo in 2016, it is still struggling to cut its losses. In the September quarter of FY23, it brought down its losses to $6.8 million from $8 million YoY on the gross booking value of $1.5 billion.

Most online travel portals in India, with the exception of EaseMyTrip, are in the red despite raising enough capital to drive volumes of bookings. In 2017, a joint study of the Boston Consulting Group and Google projected the Indian travel market to reach a size of $48 billion by 2020, of which it expected the online travel agencies to corner 40% to 50% of the share. Consulting firm Praxis Global made a more conservative estimate of the online travel market to stand at $13.6 billion by 2021. Despite this large share, online travel companies continue to struggle in their account books.

This duality is peculiar to India, since the original Western models have not travelled on this kind of long road to profitability. Booking Holdings, the parent company of Booking.com, posted a net income of $1.17 billion in 2021. Interestingly, it was founded only four years before MakeMyTrip started its operations in the US.

Shivani Arora, a professor at Shaheed Bhagat Singh College, University of Delhi, has studied the rise of online travel industry in India. Though optimistic about the growth of the industry, she explains the duality of high revenue and no profit in it. She says, “The enigma of increasing revenue and posting losses may seem mind-boggling, but it is a simple phenomenon. The revenues are reinvested in the diverse portfolio, as the unique Indian customer requires that. Oyo Rooms’ unique concept of economy accommodation was integrated by MakeMyTrip, as it did with Airbnb-type stays. The latest trend of superapp has stung MakeMyTrip as well. So, providing all travel-related services will require the acquisition of new companies and the expansion of existing businesses.” She adds that the Indian customer always seeks discounts, which affects a company’s margins. However, she feels that these companies will grow further, which will retain the interest of investors in the sector.

Ecommerce Bleeds White

When Flipkart was founded in 2007 with the aim of being India’s Amazon, not many internet users had started making purchases online even though many rudimentary ecommerce portals had been around for years. One could argue that the ecommerce as a business sector developed in India as Flipkart went from strength to strength. By 2012, it was a unicorn, the third in India then after MakeMyTrip and adtech venture InMobi. It exposed hundreds of traders and millions of users to ecommerce and spawned competition that included its inspiration Amazon. The global retail giant entered India as a marketplace in June 2013, a good nine years after it started operations in China.

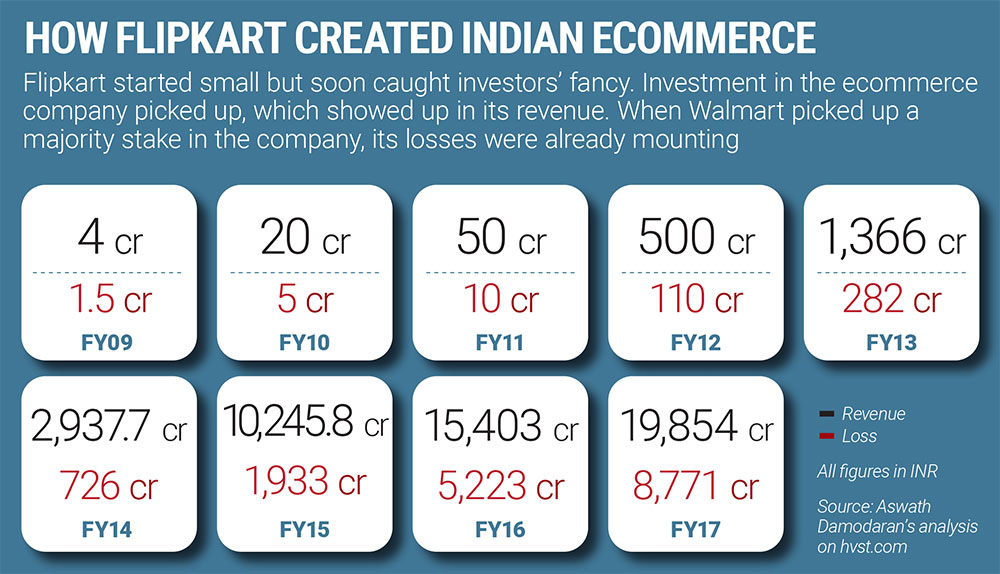

Flipkart kept raising money from global investors over the years and expanding from metros to Tier II and Tier III cities. Both its revenue and losses grew exponentially as its userbase increased. In its first full year of operation in FY09, it had posted a loss of Rs 1.5 crore on a revenue of around Rs 4 crore. That was a net negative margin of 37.5%. In the next few years, it seemed to work hard to cut losses, which it brought down to 18.8% in FY15 on a revenue of Rs 10,245.8 crore.

By then, Amazon had started giving stiff competition to Flipkart with its seemingly unlimited source of funds and global experience in managing supply chains and a buyout by Walmart was just three years away. These factors added to the aggression visible in Flipkart’s strategy in the next two years. In FY17, the Indian ecommerce giant had earned a revenue of Rs 19,854 crore. However, it also increased its losses to Rs 8,771 crore at a net margin of –44.18%.

Nothing much seems to have changed for the company even after Walmart bought a majority stake in it, with many subsidiaries of Flipkart posting increase in both revenue and losses year after year. Aswath Damodaran, professor at the Stern School of Business at New York University, showed in a 2018 study that Walmart’s operating margin stayed in the positive above a comfortable range of 5% from the 1990s till 2017. The global comparison highlights the inability of the Indian ecommerce leader to earn returns for its main investor. It is ironical, however, that its valuation keeps rising every year. In 2021, it was estimated that Flipkart was worth more than $37 billion.

The size of Flipkart’s losses apart, a more symptomatic story of India’s digital dream losing steam could be seen in the performance of the Amazon’s Indian arm. Amazon India started operations in India with fanfare. Its then CEO Jeff Bezos came to India, famously rode a decorated truck and announced a series of investments in its Indian operations. However, its marketplace business continues to post losses, even when its cloud business has a sizeable market share in India. The global ecommerce leader first bit the dust in China and lost ground to local competition and then trailed the clone Flipkart in India.

In FY22, Amazon India took solace in the fact that its revenue from the marketplace business went up substantially from FY21—from Rs 16,378 crore to Rs 21,633 crore—and it cut losses in the same period by 23% to Rs 3,649 crore. However, its ecommerce business, like Flipkart’s, shows no sign of turning profitable.

Arvind Singhal, chairman of Technopak Advisors, explains the travails of ecommerce in India. He says, “The physical merchandise market in India is $850 million. The ecommerce market in that would be about $40 million to $45 million, which is just about 5% of the total market. In most of the countries, it has moved beyond 10%–15%. So, the market in India is quite small. It is also a poor market as far as purchasing power is concerned. The average ticket size for transactions is mostly below Rs 1,000.”

Though Amazon India has had trouble with the government and rival Reliance, especially with the latter’s deal with the Future Group, its problems in the ecommerce business seem more sectoral in nature than caused by extraneous factors. Globally, Amazon’s ecommerce business continues to ride the profit wave. Barring the two bad quarters in 2022, its net profit continues to grow. It stood at $2.9 billion in Q3 2022 after seeing a massive churn at $14.3 billion in Q4 2021. In Q3 2022, more than 40% of Amazon’s global business came from its online stores.

The Unicorn Burden

The year 2021 saw a record investment in Indian start-ups from venture capital funds, a lot of which operated in the digital space. This investment and the continued momentum in 2022, albeit at a slower pace, pushed the number of Indian start-ups to the triple-figure category. The National Investment Promotion and Facilitation Agency claims that India added its 107th unicorn in September 2022, and many research agencies claim that the country has the third largest number of unicorns in the world after the US and China.

The exact number of unicorns in India is a matter of debate, as their valuation keeps changing and the methodology employed by different organisations to count such companies also has variance. Incidentally, data compiled by the media organisation Finbold claims that in November last year, the number of unicorns in India had dropped to 85, though the top three slots in the list of countries with the highest number of unicorns did not change.

If one takes the health of unicorns as a barometer for the status of the digital economy in India, since most of these companies are either tech driven or have a sizeable presence in the digital space, the story of the fast-expanding digital economy makes for a curious reading.

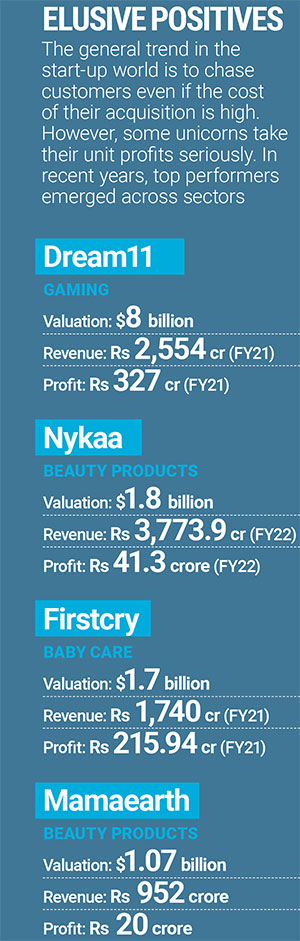

Nearly two decades after the country’s digital economy started taking shape, the biggest of its digital start-ups either continue to play the valuation and customer-acquisition game or are posting meagre profits. In fact, higher the valuation, higher is likely to be the losses of these unicorns. According to market research company Venture Intelligence, India has seven unicorns with a valuation of $8 billion and above, which include Flipkart, Byju’s, Paytm, Swiggy, Polygon, Oyo Rooms and Dream11, out of which only Dream11 posted profit in the last two years—it reported FY21 profit at Rs 327.1 crore, with. its current valuation is at $8 billion—while the revenue and profit or loss figures of Polygon are not available in the public domain. Edtech company Byju’s, which is on an aggressive acquisition spree, posted a loss of Rs 4,588.75 crore in FY21 while it stands at a valuation of $22 billion currently.

Logic of Digital Profit

The story of the success of the Indian IT industry has been told before. The rate of its revenue, profit and job creation only competes with itself. Whatever little stagnation was visible in this sector before Covid-19 hit the world has been reversed. The revenue of the Indian IT sector is picking up again on account of increased digitalisation and has already crossed the $200 billion mark in FY22.

Similarly, some of the earliest companies that operated in the digital domain continue to make profits. Info Edge, which runs the popular portals Naukri.com and Jeevansaathi.com, is consistent in posting quarterly profits. It declared a profit of Rs 93.9 crore in Q2 FY23. Its consistent growth allowed it to become an investor in other start-ups, the prized one of them being Zomato, especially after it went public.

The unicorns that seem to be doing relatively better in terms of making profit or cutting losses exist in scattered niche segments, like in the online gaming space, Dream11 and Games24x7 posted profit in FY21. However, the latter posted a loss of Rs 230 crore in FY22 after declaring two successive years of profit. Similarly, in the niche ecommerce space, Nykaa, FirstCry, Mamaearth and Lenskart reported profit in FY21. By the time FY22 ended, Lenskart had slipped into the red. It reported a loss of Rs 102 crore after posting a profit of Rs 28 crore in FY21, possibly on account of its expansion in Southeast Asia. Interestingly, all of them have a hybrid approach to retailing, with both ecommerce and physical stores being part of their expansion and consolidation plans.

The unicorns that seem to buck the trend are in the finance and markets segment—with Zerodha, CoinSwitch Kuber and RazorPay not only retaining their leadership position but also reporting profits—and SaaS space, like Zoho.

The narrative that emerges from an analysis of India’s digital economy is that its digital companies are taking very long to cut losses even when the country’s digital economy is expanding rapidly. The situation is particularly dismal where start-ups play fully digital and it improves only when a hybrid approach is taken. The digital disruption in India, thus, stays funded.

—With input from Pallavi Chakravarty

Credit: Source link

Comments are closed.