UK startup Lawhive has 31 individual angels and two institutional investors — 11 times more investors than people actually working at the startup when it raised $2m in April.

“It’s been like having a panel of the best top advisors in the world, who also happened to invest in the company,” says cofounder and CEO Pierre Proner.

Lawhive’s angel investors include Bloom & Wild CEO Aron Gelbard and fintech soonicorn Primer’s cofounders. Proner has even made an Airtable that lists each angel’s areas of expertise so he knows exactly who to reach out to for what.

And he’s not the only European founder with a tonne of angels on his cap table.

If you don’t have more angel investors than wedding guests, are you missing out?

Early-stage founders in Europe’s top hubs are increasingly bringing on several, if not dozens, of startup operators and founders as investors thanks to a new generation of tech platforms.

These companies make it easier to pool small investors into one cheque — otherwise known as a special purpose vehicle (SPV) — and drastically reduce the admin hassle and costs associated with bringing on additional investors.

It’s quite a change of strategy: in the past, founders generally tried to limit investor numbers.

“People were cautious about having lots of people on the cap table, and VCs pretty strongly advised against it. I think part of that was because of the admin around getting lots of signatures,” says Hector Mason, partner at VC firm Episode 1 Ventures.

“But it was overlooked that actually, those people on your cap table could be really valuable to you and that value might actually outweigh the admin burden.”

Founders say that “value” can include introductions to clients and potential investors or just advice with the day-to-day of running a business. Marius Hepp, cofounder of Berlin’s Junto, a B2B upskilling platform, told Sifted he has more than 50 angel investors, who he’s hoping will help the company get access to potential clients and potential instructors at fast-growing tech companies.

The new tech platforms making having many angel investors possible

One of these platforms is Odin. It helps angel investors invest as a group, or syndicate; it says there are roughly 10-15 angels investing together per deal put together on its platform. Another popular platform is Vauban, which was bought by US fintech Carta earlier this year.

Junto used Bunch — a similar platform, which raised a €7.3m seed round last month from Cherry Ventures — to take investment from its 50+ angels. And in a very meta move, Bunch used Bunch to raise investment from more than 25 angels worldwide.

Pooling angels together isn’t just useful for startups. It also makes it possible for angels who can’t write five or six-digit cheques to invest in funding rounds, opening up angel investing to a much bigger group of people — including founders and operators who haven’t yet had a big cashout. Odin says that the median ticket size on its platform is £3,000.

“I’m not an exited founder so £5,000 to £10k investments? I would only be able to make maybe one or two a year. And I knew that I needed to make like 20 for it to really make sense [given the risk profile of startup investments],” says Anthony Collias, a London-based entrepreneur who now invests with other angels using Odin.

Collias had dealflow from his network, and friends with the money to angel invest, but he wasn’t able to bring those two together until Odin made it possible with lower fees and by allowing smaller individual cheques. Now, his syndicate invests about £20k on average per deal, with individuals contributing between £1,000 and £15k each. He says the group expects to do five to ten deals a year.

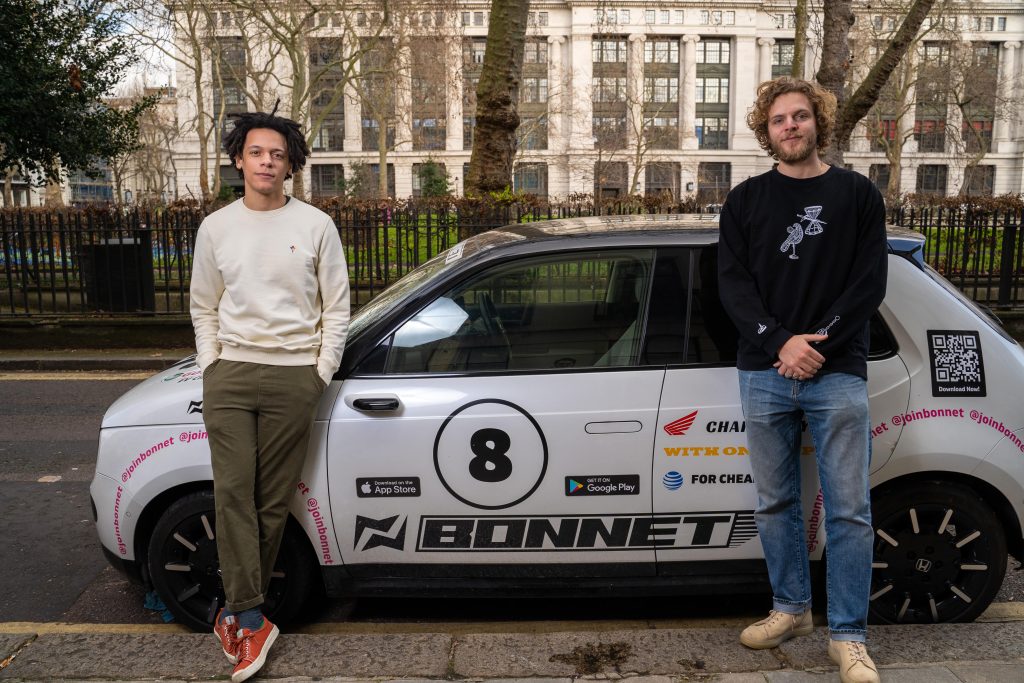

The Stage, a UK-based demo day that puts early-stage startups in front of VCs, also uses Odin to bring angel investors into its deals with as little as £1,000, says Episode 1’s Mason, who also runs The Stage. One company, EV charging startup Bonnet, raised investment from 29 attendees at a demo day last year and went on to raise €5m from Lightspeed, GV, 20VC and APX.

But what do the angels get out of it?

One of those individual investors in Bonnet was Harry Nightingall, a product manager at Expedia who has been investing in startups since he stumped up £10 in a crowdfunding campaign on Crowdcube in 2011.

Unlike crowdfunding, where you might be one of thousands of investors, he says doing angel investing gives him a way to learn and give back — by providing advice on product, for example.

Collias is also partly in it for the learnings. “I find out about what’s going on in a founder’s business, and some of the dynamics within a market that I’m not involved in,” he says. “I think it’s 50% genuinely a good personal investment strategy, and 50% it’s fun, interesting and a way to build a network.”

Others feel like it’s a way to support diverse founders at the earliest stages who might not have access to investor networks or information.

“I spend quite a lot of time with female founders at the pre-seed stage doing pitch practising, putting together lists of who they should talk to in order to raise their first round of funding and helping them think through their business model,” says Natasha Jones, an investor at Octopus Ventures and an angel investor on the side.

She started investing as an angel about a year and a half ago — although her day job as a VC means she can only back companies that wouldn’t be a fit for her team at Octopus.

“I also want to help them understand the lens through which they’ll be assessed by future investors,” she adds.

The increasing ease of investing as a group and pooling smaller cheques is also bringing more diverse investors to angel investing. Andy Ayim runs the Angel Investing School, a programme to train up new angel investors. He recently brought together a group of eight Black angel investors in the UK to back a business called Ava Estell, a direct-to-consumer skincare company founded by Ghanaian entrepreneur Yaw Okyere. It raised £126k from an SPV formed by the angels.

Ayim says he brought the group of investors together “through just a handful or WhatsApp messages to new and experienced angel investors” in his network. He adds that an SPV “personalises” an investment, allowing founders to leverage the angels’ network and form close relationships with the angels.

“It also really changes that power dynamic,” he says. “The founder is the one who has taken the leap of faith and who’s taking the financial risk on. We have the privilege to support them if they allow us to. Rather than the opposite of that dynamic where the founder feels like they need the investment [and are privileged to receive it].”

Eleanor Warnock is Sifted’s deputy editor and cohost of The Sifted Podcast. She tweets from @misssaxbys

Credit: Source link

Comments are closed.